This is the first in a short series introducing Knowledge Graphs. It covers just the basics, showing how to write, store, query and work with graph data using RDF (short for Resource Description Format). I will keep it free of theory and interesting but unnecessary digressions. Let me know in the comments if you find it useful, and also tell me what other Knowledge Graph topics you would like to know more about.

This post shows some of the basics of RDF and knowledge graphs. It introduces the simple idea of the triple, how you make statements with them, and piece them together into graphs. I show how you can neatly write RDF using the Turtle language as well as how to use the elegant query language SPARQL to explore your knowledge graph.

- Knowledge Graphs 101

- Knowledge Graphs 2 – Playing on the CLI

- Knowledge Graphs 3 – Using a Triple Store

- Knowledge Graphs 4 – Querying your knowledge graph using .NET

- Knowledge Graphs 5 – Modelling with RDFS

- Knowledge Graphs 6 – Semantics

- Knowledge Graphs 7 – Named graphs

RDF Triples – The Lego Blocks

RDF is a way to represent graphs using triples made up of Uris for both vertice and edges. A triple consists of three parts: Subject, Predicate and Object. The subject is the primary thing that you are making a statement about. The Object is something that you are relating to the Subject, and the Predicate is how you are relating the Subject and Object.

Let’s take some concrete examples.

“The cat sat on the mat“

In triple form, this might be represented as:

(the cat, sat on, the mat) .

Let’s try another:

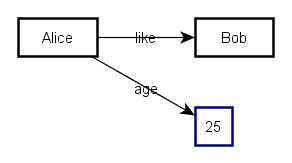

“Alice likes Bob“

(Alice, like, Bob)When you want to say something quantitative, you can still use triples:

“Alice is age 25“

Which we say like this:

(Alice, age, 25) .

I changed the colour of 25 to highlight that it is a “Literal” which means an item of data rather than a resource. Typically, it cannot be the subject of a triple, the way URIs can.

Because we can keep adding vertices and edges to this graph, there’s really no limit to what we can store or represent. In fact, there’s a well known principle of knowledge graphs, called the “AAA Principle“, that says Anyone can say Anything about Any topic. Obviously, when we are working within a bounded domain, we restrict ourselves to a specific subset of the data. But over time we will encounter more and more data sources. And those data sources can also be integrated with our data to allow us to enrich our data without limits.

For now, it just means you can store anything in a triple store, and probably will given enough time. And that’s a good thing!

Conventionally, we represent the contents of the graph DB as a table of Subject, Predicate and Object triples:

| Subject | Predicate | Object |

|---|---|---|

| Alice | like | Bob |

| Alice | age | 25 |

So long as we break down our knowledge into triples like this, we can represent pretty much anything in the graph DB.

In practice, as with relational databases, the way data is actually stored varies widely between vendors and is often a closely guarded secret. These days, it’s reported that the performance of triple stores and graph databases generally is approaching that of relational databases.

I mentioned earlier that the main components of a triple in W3C Knowledge Graphs are URIs. So our triple is more likely to look like this:

<http://tempuri.com/people/Alice> <http://example.com/relationships/likes> <http://tempuri.com/people/Bob> .Just like with XML documents, you can define a set of URI abbreviations – called Namespace Prefixes – that allow a more readable format:

@prefix p: <http://tempuri.com/people/> .

@prefix r: <http://example.com/relationships/> .

p:Alice r:like p:Bob .

I’m trying to avoid theory, so let’s just say that using URIs helps when you need to link to other people’s data, and integrate data without various kinds of clashes.

A a knowledge capture platform, RDF would not be very interesting, if you could only say one thing about a subject. Here’s how you can say a bunch of things together:

p:Alice rdf:type p:Person;

r:like p:Bob;

r:givenName "Alice";

r:familyName "Brown";

r:age 25 .

Using a semicolon, means we are going to follow on with another statement about this Subject, providing only the Predicate and Object parts of the triple. So we just made 5 different statements about p:Alice there.

We might also want to reuse the Subject and the Predicate for later assertions:

p:Alice r:like p:Bob, p:Charlie, p:David, p:Eddie, p:Fred .

Again, another 5 statements of the form p:Alice r:like ?someone . Where ?someone comes from the list of people at the end.

This language I’ve been describing is called Turtle – short for Terse RDF Triple Language. It’s a nice clean way to write RDF, and a good place to start. It’s not the only one though – there are others that suit different use cases – and we’ll visit them another time.

Putting data into a database is all very cool, but only if you can get it back out again. The query language for W3C Knowledge Graphs is called SPARQL. It’s designed to look a lot like SQL, but to me it’s so much better – a thing of beauty and power.

Here’s how we find out who Alice likes.

SELECT ?person

WHERE {

p:Alice r:like ?person .

}

This query uses pattern matching to find all the triples matching that Graph Pattern. Just like Prolog, it searches for triples that fit the slots in the Graph Pattern.

?person |

|---|

p:Bob |

p:Charlie |

p:David |

p:Eddie |

p:Fred |

The thing I love about SPARQL is that the format you query with is the same as the data you put in a get back. You just describe the shape of the data you want out, filling in what you know, and creating blanks – variables – for what you don’t. This scales nicely above and beyond what would be hairy in SQL.

Here’s a query that shows how a graph pattern acts as a kind of rich filter – show me the people who are liked by other people who are 25 years old.

SELECT ?person

WHERE {

_:liker r:like ?person ;

r:age 25 .

}

Laughably simple, huh? Let’s make our graph a bit richer.

p:Alice r:like p:Bob, p:Charlie, p:David;

r:givenName "Alice";

r:familyName "Brown";

r:age 25 .

p:Bob r:like p:Alice, p:Charlie, p:Eddie;

r:givenName "Bob";

r:familyName "Carter";

r:age 31 .

p:Charlie r:like p:Alice, p:Bob, p:Eddie, p:Fred;

r:givenName "Charles";

r:familyName "David";

r:age 27 .

p:David r:like p:Alice, p:Bob, p:Eddie, p:Fred;

r:givenName "David";

r:familyName "Eddings";

r:age 28 .

p:Eddie r:like p:Alice, p:Bob, p:Eddie, p:Fred;

r:givenName "Edward";

r:familyName "Foster";

r:age 28 .

p:Fred r:like p:Alice, p:Bob, p:Eddie, p:Fred;

r:givenName "Frederick";

r:familyName "Groves";

r:age 25 .

Show me the people who are 27, who are liked by a person that is 25.

SELECT DISTINCT ?person

WHERE {

?person r:age 27 .

?x r:like ?person;

r:age 25.

}

> p:Charlie

Just state in the graph pattern what must be true about the results, and leave the rest blank (by adding variables that begin with ‘?‘). It pretty much is as simple as that. So much easier to build up a complex query.

Summary

This post showed just the basics of RDF and knowledge graphs. It introduce the simple idea of the triple, how you make statements with them, and piece them together. I showed how you can neatly write RDF using the Turtle language and how to query using SPARQL to explore your knowledge graph.

Next time, I will show how to play with RDF on the command line, and also how to call out to AWS Neptune using .NET. Please let me know if you found this helpful. This is a work in progress, so please let me know what would help to make your journey into knowledge graphs easier and I’ll try to include it in a post.

You must be logged in to post a comment.